Illinois Governor Signs Medical Aid in Dying Law, Effective 2026

Illinois Enacts Medical Aid in Dying Law

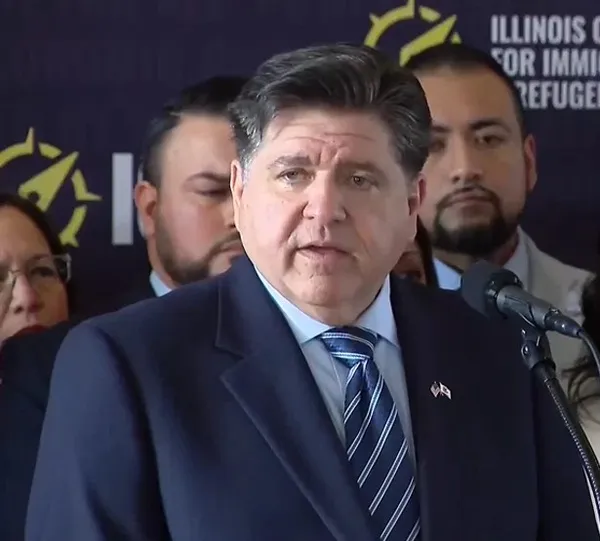

On Friday, Illinois Governor JB Pritzker signed the “Medical Aid in Dying” bill, also known as “Deb’s Law,” into law in Illinois. The legislation allows certain terminally ill adults in the state to seek and take prescribed medication to end their own lives.

With the signing on December 12, Illinois joins several other states that have enacted similar medical aid in dying legislation. The law is scheduled to take effect in September 2026. Lawmakers state that the delayed start date is intended to give participating health care providers and the Illinois Department of Public Health time to implement the processes and protections required under the law.

Key Provisions for Patients

The law permits a patient to obtain and self-administer life-ending medication if the patient meets several criteria. The patient must be at least 18 years old and have a terminal illness that is expected to result in death within six months, as determined by two physicians. The attending physician must inform the patient about all end-of-life care options, including comfort care, hospice, palliative care, and pain control.

Under the legislation, the physician must confirm that the patient has the mental capacity to make medical decisions. The law requires patients to make multiple written and oral requests for the life-ending medication. Only the patient can make these requests; surrogates, health care proxies, health care agents, attorneys-in-fact for health care, guardians, or advance care directives cannot request the medication on the patient’s behalf.

Requirements and Protections for Physicians

Attending physicians must provide informed consent about appropriate end-of-life care options and conduct an in-person exam to determine whether the patient’s illness will result in death within six months. Two doctors must agree on this prognosis. The physician must also determine that the patient is not under undue influence. If there are concerns about the patient’s mental fitness, the patient must be referred to a licensed mental health professional. A patient found by the mental health professional not to have mental capacity does not qualify under the law.

If a patient uses the end-of-life option, physicians are required to submit information within 60 days after the patient’s death to the Illinois Department of Public Health. That information must include details about the patient, the diagnosis, confirmation that legal requirements were met, and notice that medication was prescribed in accordance with the Act. The law states that this information is confidential, privileged, and not discoverable in civil, criminal, administrative, or other proceedings.

Participation, Insurance, and Legal Constraints

The legislation specifies that no physician, health care provider, or pharmacist is required to participate in the medical aid in dying process. It establishes that coercing someone to request the medication or forging such a request is a felony. Health care entities are permitted to prohibit their staff from participating in activities authorized by the Act while working for those organizations.

The law further provides that insurance plans, including Medicaid, cannot deny or alter benefits for a patient with a terminal disease based on the availability of medical aid in dying, a patient’s request for the medication, or the absence of such a request. At the same time, the law does not require private insurers or Medicaid to cover the care authorized under the Act.

Advocacy and Opposition

Compassion & Choices, an organization dedicated to expanding options for end-of-life care, has stated that it plans to pursue medical aid in dying legislation in Connecticut, Massachusetts, Minnesota, Maryland, Virginia, and Florida next year. According to the organization’s website, its goal is for 50 percent of all Americans to live in states where medical aid in dying is authorized by 2028.

One of the most prominent advocates for the Illinois measure is Deb Robertson, a lifelong Illinois resident who has a rare terminal illness. Robertson stated that she is pleased to have been able to help ensure that terminally ill residents of Illinois will have access to medical aid in dying.

The bill, designated SB 1950, faced objections prior to its signing. Several coroners, medical experts, religious communities, and disability-rights advocates raised concerns about the legislation. The Catholic Conference of Illinois called on the governor to veto the bill and advocated expanding palliative care programs as an alternative. After the bill’s passage in October, the Catholic Conference stated that many lawmakers did not adopt palliative care as an alternative to assisted suicide.

Following Governor Pritzker’s approval of the measure, House Minority Leader Tony McCombie released a statement opposing the legislation and asserting that coroners, who will determine causes of death, were not included in discussions. The Thomas More Society, a national not-for-profit law firm, also issued a statement condemning the new law and asserting that it places elderly, disabled, and vulnerable individuals at risk.

COMMENTS (0)

Sign in to join the conversation

LOGIN TO COMMENT